The grounds here are so impressive that it might be easy to miss this unassuming statue, tucked away beside the grand marbled steps leading to the Alabama State Capitol Building in Montgomery. The towering columns and neatly manicured hedges that frame the statue fail to encapsulate the impact of the man immortalized here since 1939. The man is white, holding one hand on his cane and the other, his lapel. The inscription informs us that he is the “Father of Modern Gynecology.”

180 years ago and 5 blocks west of the statue, the man in the statue would have come to life as he entered his office at 32 Perry Street. The streets would be bustling with activity. Just around the corner at Fountain Square was the auction block where dozens of enslaved people would be getting sold. Many of the buildings surrounding this medical office were sites where enslaved people were warehoused. Through the windows an enslaved woman might be seen being led to the back of the brick building.

J. Marion Sims moved to Alabama in 1840 after failing in Pennsylvania. In Montgomery, he worked as a plantation physician, “treating” enslaved women. Enslavers sent women to him when pain affected their labor. He wrote, “I made this proposition to the owners of the negroes. I agree to perform no experiment or operation on either of them to endanger their lives, and will not charge a cent for keeping them, but you must pay their taxes and clothe them.” At least 11 women were subjected to his procedures, but only three names are known: Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey.

As context, doctors often worked with enslavers to assess the “fitness” of enslaved people for auction. Their care prioritized protecting enslavers’ investments over the relief of suffering. In 1807, Congress banned the importation of enslaved people, shifting the burden of reproduction onto Black women. They were forced to bear more children to sustain plantation economies. This led to increased medical experimentation on Black women, aimed at accelerating childbirth and ensuring their reproductive capacity, marking a dark era of exploitation and abuse.

At 17 years-old, Anarcha suffered a traumatic birth, leaving her with a vesicovaginal fistula, common among enslaved women denied medical care. Sims experimented on her without anesthesia at least 30 times, often on display for observing colleagues. Notes indicate that her cries overwhelmed his assistants. Eventually, the enslaved women had to restrain one another. Many women died, but Sims blamed them, not himself. His reputation as the “father of modern gynecology” was built on the torture of Black women. This was the cost of developing the Sims speculum, a tool still widely used today by doctors to examine the vagina and cervix.

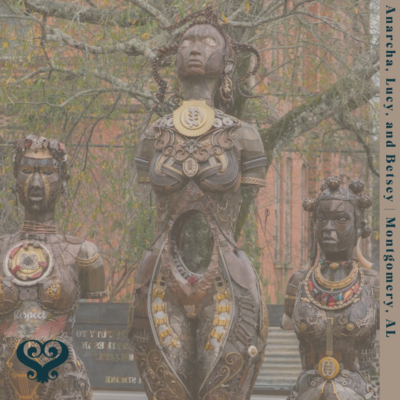

J. Marion Sims’ legacy embodies a broader disregard for Black life in medicine. His experiments, violating “do no harm,” reflect systemic racism and sexism. Black women still face disparities in reproductive care, from maternal mortality to life expectancy. Sims remains celebrated in places like Montgomery, where a statue honors him in front of the Alabama State Capitol. However, a new monument nearby created by artist activist Michelle Browder recognizes the sacrifice of Anarcha, Betsy, and Lucy. Their story is a reminder of medicine’s troubling history and ongoing inequities to exist in this country.