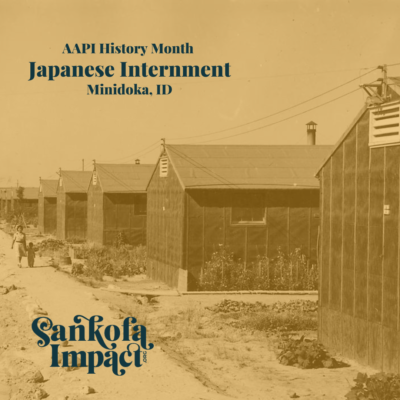

In the Magic Valley of southern Idaho, there is a wide open stretch of land with dry grass that waves in a hot breeze. A marshy canal runs through this area, winding through a few weather-worn wood barracks scattered across the property. Near the perimeter, corroded barbed wire lies in mangled piles upon the ground. The space here in Minidoka, seems like the only occupants left must be the ghosts of the past residents.

In August of 1942, this area would have been swarming with thousands of Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans. 9,397 people would be living and working as farmers at this site, under the watchful glare of American soldiers armed with machine guns, some watching from a tower at the entrance of this concentration camp. One such story can be found in Louis, a young Japanese-American man, born in Walnut Creek, CA in 1916.

Louis was a skilled artist and despite only having a 6th grade education, he dreamt of one day enrolling in college to be an art student. At the age of 21, Louis said goodbye to his family in California and made his way to Seattle in the hope of finding work in the fishing industry. Through a marriage arranged by their parents, Louis and Mieko began their lives. As anti-Asian sentiments began to worsen, Louis soon sent Mieko and their children to live in Japan with family.

In May of 1942 Louis packed a single suitcase and boarded a train headed to the Puyallup Fairgrounds, along with thousands of other Japanese people. Camp Harmony, a name coined by an Army public-relations officer, temporarily housed more than 7,000 Seattle area Japanese-Americans while they awaited their systematic eviction to internment camps. Louis was scared, angry, and confused as he sat on an army cot that would serve as his bed before being transported to Minidoka, Idaho.

In December 1941, Japanese Armed Forces infamously bombed a US Naval base in Pearl Harbor, Hawai’i. Following this tragic event, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, placing all people of Japanese descent in concentration camps. Over the course of World War II, ten camps would be completed in remote areas of seven western states, including in Southern Idaho at Minidoka.

Life at Minidoka was harsh. Louis lived in one of 36 residential blocks, each block containing 12 barracks, a mess hall, and a latrine. Within the barracks, Louis would have resided in one of the 6 units with another family or a group of individuals. There were 489 births and 193 deaths at Minidoka, which constituted the 7th largest city in Idaho while it was operational between 1942 and 1945. After being released, Louis moved back to the Puget Sound area.

Today’s impact of the internment of Japanese Americans can be found in the long-term health consequences caused by their treatment in the camps. Survey data has found that former internees had a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, mortality, and premature death than their non-interned counterparts. When the U.S. government finally issued an apology and reparation checks of $20K to those Japanese-American citizens impacted by the internment, so much had already been lost.

Louis is the grandfather of Sankofa Impact’s Executive Director, Felicia Ishino. The trauma that Louis lived through directly and indirectly impacted his family. The phrase, Shikata ga nai roughly translates to, “nothing can be done about it.” Upon Louis’ return to Seattle, everything had changed. His home and community were gone. Shikata ga nai. Somewhere along the way, Louis Ishino vowed to never discuss his traumatic experience at Minidoka. Shikata ga nai.